by Christina Lynch

The first draft of my novel Sally Brady’s Italian Adventure was actually set in 2041, during an imagined World War Three. I created a future where Europe, including Italy, had slid into war when Russian fascism took hold following the covid pandemic, and a Putin-like figure and his Italian rival, whom I named Massimo Castracani, used nationalism and propaganda to expand their empires. I finished the draft at the end of 2020, right before January 6 happened, a year before Russia invaded Ukraine, and just under two years before Italy elected a neo-Fascist prime minister. No, I didn’t have a crystal ball—I just made some lucky guesses when reading the media tea leaves. That happened once before, actually. My first novel under my own name, The Italian Party, follows an inept CIA operative in Siena in 1956 as he tries to throw a mayoral election. How would one do that? I asked myself, and proceeded to invent honey traps, smear campaigns, and false flag attacks. I sold that novel in September of 2016 and less than a month later, when news came out about Russian attempts to influence the US Presidential election, my new editor asked me “How did you know that was going to happen?”

History repeats itself, goes the cliché, or as Churchill put it, “Those who fail to study the past are condemned to repeat it.” Karl Marx had a darker take on the idea: “History repeats itself, first as a tragedy and second as a farce.” Mark Twain’s purported version was “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” (That sounds like something Chat GPT would do.) Yet no matter how often great minds repeat the idea that we should not repeat our pasts, it doesn’t seem to sink in.

My publishers asked me to move Sally Brady a hundred years back in time, to the 1940s. Their argument was that it felt heavy handed to portray the world as sliding into a WWIII that so closely resembled WWII. Better to write about WWII and let readers draw their own parallels. After moaning and groaning a bit, I decided they were right. It took me a year to revise the novel and reset it in the period from 1931-1947, and I was able to include very specific true details about what it was like to live with rising Fascist power—the role of propaganda, the allure of nationalism, the way violence became normalized—and also portray the efforts of those who pushed back in large and small ways. Plus, it was satisfying to write about (spoiler alert) Mussolini’s defeat, humiliation, and death.

I created three characters through which the reader could experience what it felt like to slide into authoritarianism and war. Sally, a young American gossip columnist who’d be right at home on Instagram or TikTok, thinks Mussolini is a glamorous and slightly comical figure, as so many Americans at the time did, until his thugs jail her. Lapo, a good-hearted, middle-aged Italian writer, is married to an American and has a son of draft age. To help his friends and family, he finds himself pressed into becoming part of the Fascist propaganda machine, and even running a camp for political prisoners. His character is the most chilling for me—while Sally can fight back because she has only her own life to lose, Lapo must make impossible decisions to save the lives of others. Lapo’s son Alessandro, an anti-Fascist activist who is drafted into the Italian army and stationed in Prague, is pushed to his moral breaking point.

So many times when writing the novel I saw echoes of the 1930s in the news of today. I would be reading a book or article about how Mussolini took control of newspapers, and then click over to the New York Times home page to find a piece about Putin doing the same in Moscow, or our own president calling the press “the enemy of the people.” I was most chilled by the way Mussolini turned his citizens on each other, encouraging them to rat out their friends and neighbors in a system of schedature, card files detailing even minor statements criticizing the regime. I thought of how smart phones listen to us constantly, how China weaponized them against the Uighurs, and Putin uses social media to disinform. Italy under Mussolini was all about seeing your leader as a god, your neighbor as your enemy, and violence as patriotism—at the end of a writing day, my hair was often on end. To counteract my own dread, Sally grew smarter and stronger and more courageous and more selfless. She became what I hoped I would be if I were living under Fascism, while all the while worrying I was much more likely to be poor Lapo, making small decisions that seemed right at the time but that would lead to terrible outcomes.

I wrote Sally for readers who might not know history that well, or even be very interested in it. Readers who might, while being entertained by the story of a clever young woman who finds herself behind enemy lines armed with nothing but lipstick and a sense of humor, learn something that would make them recognize echoes of past mistakes in our time, and recoil from them.

Sally Brady’s Italian Adventure is ultimately an uplifting book, even as it adds its voice to the chorus of those begging us to study history in order not to repeat it. Sally remains optimistic about the world, even as it falls apart around her. She finds joy in connection with others, and family in unexpected places. In writing her story I found solace in a character who uses her intelligence and her wit to stay alive and help others—and who is in turn helped by others who don’t care about her last name or her birthplace or her passport or any of the ways identity is used to divide us. They see her as someone in need of help, like the Jewish children and adults, and downed British pilots and escaped POWs, and other “enemies” whom so many ordinary Italians risked their lives—and sometimes lost their lives—to help during the war. There is good in the world. I feel that deeply. We do not have to repeat the mistakes and atrocities of the past. And if we do find our countries repeating them, we must be Sally, and those who see in her a fellow human being worthy of love and care.

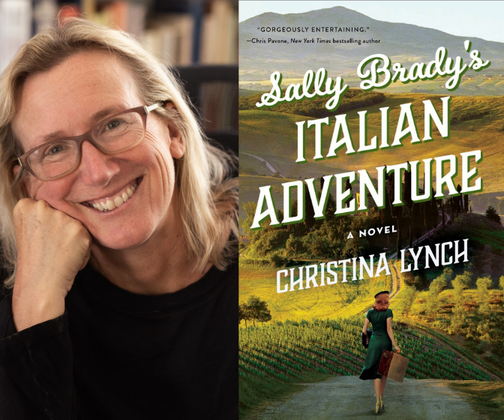

Sally Brady’s Italian Adventure releases June 13, 2023. Pre-order your copy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Christina Lynch is the author of The Italian Party (St. Martin’s, 2018) and the forthcoming Sally Brady’s Italian Adventure (St. Martin’s, 2023). Her picaresque journey includes chapters in Chicago and at Harvard, where she was an editor on the Harvard Lampoon. She was the Milan correspondent for W magazine and Women’s Wear Daily, and disappeared for four years in Tuscany. In L.A. she was on the writing staff of Unhappily Ever After; Encore, Encore; The Dead Zone and Wildfire. She now lives in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. She is also the co-author of two novels under the pen name Magnus Flyte. She teaches at a community college in central California.

Christina Lynch is available to visit with book clubs via NovelNetwork.com.